Kim Dolan has been active her whole life. Running, swimming, biking – she competed in a few triathlons, even an Ironman.

She jokes that it was to counter her occupational hazard as a pastry chef instructor at Johnson and Wales University in Providence, R.I.

The longtime AAA member also participates in the Southern New England Heart Walk, not for the exercise of the 3-mile route but to support the American Heart Association. If not for its groundbreaking research, she’s not sure she’d be here today.

So, she will volunteer for any project she can, and will tell her story to anyone to raise awareness about heart disease and the great work of the Heart Association.

‘I Couldn’t Catch My Breath’

Late in 2016, Dolan was struggling to catch her breath while exercising. She couldn’t finish a lap at her regular swim session or on her weekly 2-mile neighborhood jog with her husband.

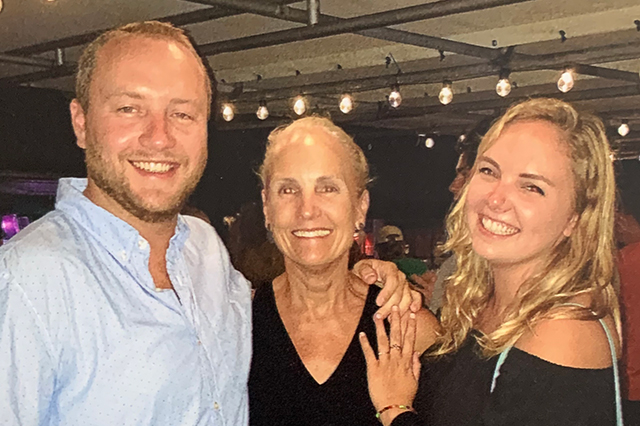

She was just tired, she reasoned. It was the holiday season, and she was busy with work, shopping and preparing for the traditional Christmas meal with her son, Maddison, and daughter, Maggie, coming in from out of state. Or maybe she was depressed – she had lost her father and her mother-in-law that year.

“I didn’t think anything of it until my husband and I were walking across the street and I couldn’t get across without stopping. I couldn’t catch my breath,” she said, “It’s hard to convince yourself you’re sick when you’re healthy in every other way. But there can be underlying things. You really have to listen to your body.”

Her husband, Mark, was so concerned he wouldn’t let her go on an after-Christmas family ski trip to New Hampshire until she had a medical checkup. Plus, he had witnessed her struggling to breathe during the night in a strange – and scary – interrupted sleep.

She drove herself to Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I., that morning. But she didn’t make it on the ski trip.

“My heart rate was 170. They put me in triage and a doctor came in right away. She did an ultrasound and found I had fluid around my heart,” Dolan said.

‘You’ve Got the Wrong Patient’

They called in a specialist from Rhode Island Hospital who ran more tests, then told her she was in heart failure and would likely need a transplant to survive.

“My whole family was there, and they were all like ‘what are you even talking about? You’ve got the wrong patient. You’ve got the wrong chart,’” she recalled.

She was transferred to Tufts Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplant Center in Boston where they confirmed the diagnosis, a rare genetic condition called non-compaction cardiomyopathy. It was a fairly new medical discovery, researched for only about 20 years.

They also determined she needed a new heart.

She was placed on the transplant list in February 2017 and sent home with a catheter in her arm to deliver medicine from a machine she wore in a purse over her shoulder. And she felt good enough to get on a treadmill and spin on a bike at the gym, until three months later, when she began feeling tired and weak again.

“So we went back to Tufts, and sure enough, my heart wasn’t doing well,” she said.

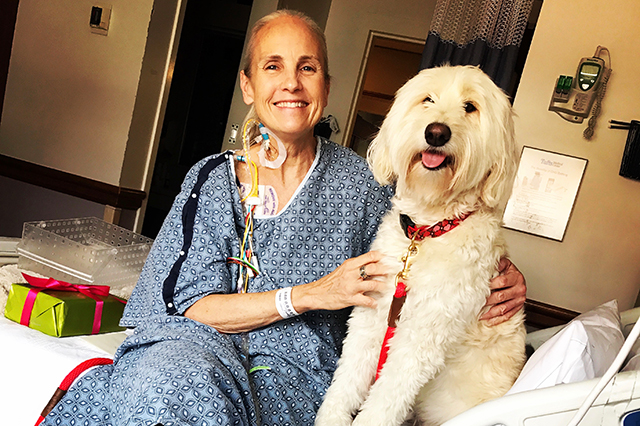

Because she was failing, she moved up on the transplant list. She was in the hospital for five weeks awaiting a heart donation, but no matches became available.

“My heart basically gave out. I had to have an emergency LVAD, which is a left ventricular assisted device. It keeps the blood flowing and pumping. That was a 10-hour surgery, and when I woke up, it was really hard,” Dolan said.

She went home again with tubes coming out of her abdomen and a battery pack the size of a laptop to keep the machine running.

‘We Have a Heart’

In late August 2017, at 2:30 a.m., she got a call from the hospital telling her a heart was available.

“So, my husband and I got in the car, and we were excited. We talked all the way to Boston – which took about 40 minutes – about all the things we were going to do, all the vacations we were going to go on, because I hadn’t been able to leave home. I had to be available within three hours if there was a heart.”

She was prepped for surgery and given anesthesia, but when she woke up, she was still attached to the LVAD. The doctor had determined that the heart was not good enough to be transplanted. After the bad news was delivered, she had to spend another five days at the hospital.

“And that was the hardest five days of the whole ordeal. I was so sad and disappointed,” she said.

In late October, she developed an infection and was back at Tufts for three days of antibiotics, then given intravenous antibiotics for home.

“All of a sudden by cardiologist walks in and says, ‘we have a heart for you,’” Dolan said.

She was also told she had the right to refuse it, because the donor had died from a drug overdose. Although the body had tested negative for HIV and hepatitis C, there was a 0.01 % chance that those diseases could be in incubation.

“He said about 35% of organ donations are coming from overdose victims because the opioid crisis is so terrible, but the organs are still viable, and those diseases can be controlled with medication,” Dolan said. “My husband asked ‘what would you do if it was someone in your family?’ And my cardiologist said ‘I’d take the heart in a second.’”

The surgery lasted 12 hours. And when she woke up, there was no LVAD. “There was just one little IV attached to me. I was able to sit up that same morning, and I was only in ICU for two days. I felt so good,” she said.

Now, she’s back on an exercise regime.

“They had me go to cardiac rehab, but I lasted just one day. I said ‘I can do better than this.’ So, I just started walking everywhere and all the time. Then I started adding things to it,” she said.

She returned to yoga and began doing Lagree, strength exercises that she prefers over cardio these days. Running isn’t appealing anymore. She’s also back to biking hard core and competed in the Transplant Games of America last summer.

And she’s thankful every day – for the heart she received from a 45-year-old woman and her family who upheld her wishes to be an organ donor. She met them two years after her transplant, and they stay in touch through Facebook.

‘What If’

Dolan now wonders about her family’s genetic history. Her father died of congestive heart failure, and his own father and mother, her grandparents, died of heart attacks.

“Did they have something similar to what I had? Maybe, if there had been more research, they wouldn’t have died at such a young age,” Dolan said.

She also wonders if she would have survived had this happened to her in college, before non-compaction cardiomyopathy was a known disease.

Her children have been tested. Her daughter carries the gene, and her son does not.

“I don’t think my condition would have been so readily diagnosed had it not been for the support of the American Heart Association. And if we didn’t have that research, we wouldn’t know that one of my children carries the gene,” she said. “She already has a cardiologist at Tufts, and it may never get to the point where it got with me. She may live forever with this.”

At AAA Northeast, we recognize that Dolan is not our only member affected in some way by heart and brain issues. We encourage all of our members to come along with us to the Southern New England Heart Walk on June 10 at Bryant University in Smithfield, R.I., or in other ways support the efforts of the American Heart Association.