Everybody loves a parade.

The celebration, the pageantry, the fanfare – it all makes for an eye-catching event that has spectators lining the streets time and again. While marching bands, balloons and other components certainly have their draw, what would a parade be without floats?

In one way or another, parade floats have existed for thousands of years. Only in the last century or so, however, have they become the intricately decorated showcases we know today.

Many of today’s parade floats are fully computerized animatronic structures. While this evolution has ratcheted up the spectacle factor, it’s also created some logistical hurdles. Most notably in moving the float along.

So, how exactly do parade floats operate? Let’s start at the beginning.

When Did Parade Floats Begin?

The origins of parade floats can be traced back to ancient Greece when statues of gods were pulled on carts. They became increasingly common in the Middle Ages, often used in plays or to celebrate kings and rulers.

Parade floats first appeared in the United States in the early 1800s. They became mainstays by the mid-century when, in 1857, New Orleans held its inaugural Mardi Gras parade. This marked the first time floats were used to celebrate the annual holiday.

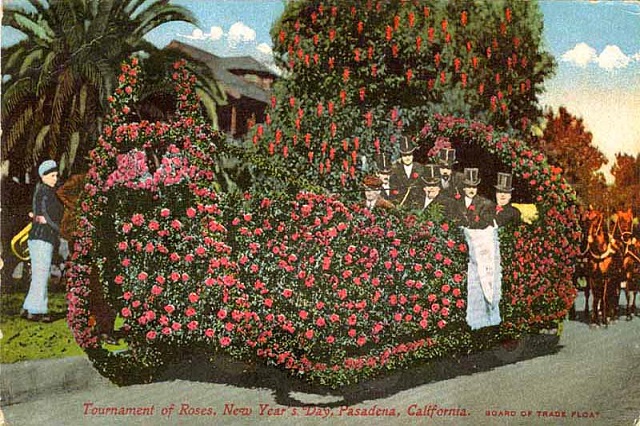

A major development in parade-float history occurred in California before the end of the century. In February 1890, members of Pasadena’s Valley Hunt Club organized an athletics competition to help promote their city. Many members had previously lived on the East Coast and invited their former neighbors to the event. To showcase the region’s balmy winter weather to its guests, the club held a parade prior to the event.

“In New York, people are buried in snow,” club member Charles F. Holder said at the time. “Here our flowers are blooming and our oranges are about to bear. Let’s hold a festival to tell the world about our paradise.” Parade entrants decorated carriages with hundreds of flowers. The spectacle led organizers to rename the celebration The Rose Parade.

Floats made a prominent appearance on the East Coast in 1924. That’s when Macy’s, which had just expanded its flagship Herald Square store to cover an entire city block, put on a Thanksgiving Day Parade to get locals in the shopping spirit. To complement its nursery rhyme-themed window displays, Macy’s created floats featuring The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe, Little Miss Muffet and Little Red Riding Hood.

How Are Parade Floats Made?

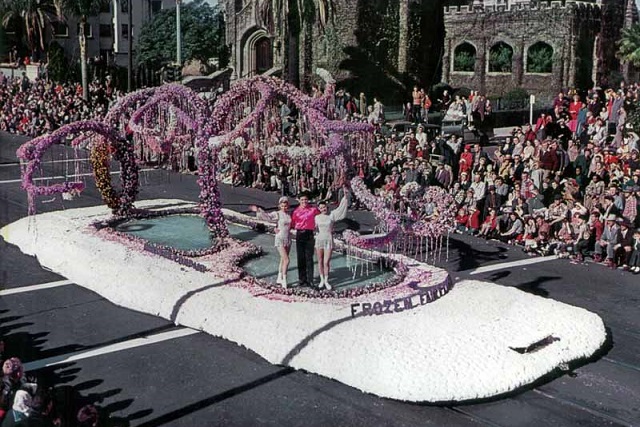

Parade floats have gone from decorated carriages to works of design and technological marvel. Today’s floats feature computer-operated animatronics and intricate decorations. Some can take up to a year to construct.

Assembling a float begins with constructing a self-propelled chassis that will support and move the structure. The float’s metal framework is built and welded to the chassis. Once the bones are in place, the entire structure is covered with aluminum wire screen and then sprayed with a plastic liquid that forms a hard skin when it dries. Any characters or props are usually made of Styrofoam and papier-mâché.

When it comes to decoration, float makers employ a wide variety of materials, including paper, wood and flowers. The Rose Parade, home to the most spectacularly decorated parade floats, requires every inch of every float be covered in a natural material.

While the emphasis is on flowers, participants often get creative. Crushed walnut shells and cornmeal, for example, can be used to replicate skin tones. Palm fibers and dried oatmeal can replicate animal fur.

How Do You Drive a Parade Float?

We’re often too mesmerized by the pageantry of a parade float to stop and think, “Wait, who is driving that thing? And how do they drive it?”

Some floats, like those appearing in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade, are pulled along by pickup trucks. Others, like those in the Rose Parade, are self-moving, controlled by a driver stationed within the bowels of the float.

Operating a float in this latter scenario is no easy job. Just getting inside is a tricky task that usually requires crawling through a hatch. Once in position, the fun begins.

There are no windshields on these vehicles. In fact, there aren’t any windows or direct views of the outside at all. Instead, cameras installed around the float feed images of the road to a screen located in front of the driver’s seat. The operator is also equipped with a headset, through which they can get instructions from spotters on the outside. These spotters walk alongside the float for the entirety of the parade.

But driving is just one aspect of operating a float. There are often a whole host of buttons, gears and switches that control different aspects of the mobile structure. The good news for the driver is that operating these is usually the responsibility of other crew members. The bad news is that as many as five people may need to squeeze into the cozy confines of the float’s chassis to get the job done.

Parade Float Factoids

- The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade’s character balloons were inspired by the Balloonatics float that appeared in the 1926 parade.

- Macy’s floats are built and stored in New Jersey. They must be broken down to travel through the Lincoln Tunnel to get to Manhattan.

- When filled with performers and guests, Macy’s Parade floats can weigh up to 8 tons.

- The longest and heaviest single-chassis parade float in the U.S. appeared at the 2017 Rose Parade. The Lucy Pet Products’ Gnarly Crankin’ K9 Wave Maker weighed more than 137,000 pounds and was over 125 feet long. It featured a 5,000-gallon water tank onboard. Eight dogs surfed in the pool as the float traveled along the route.

- Each year, it takes roughly 900 volunteer members 80,000 combined hours to construct the Rose Parade floats.

- A large Rose Parade float could contain as many as 60,000 roses.

- Floats typically travel approximately 2.5 mph.

- The iconic parade scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off in which Matthew Broderick sings on top of a float was shot during an actual parade.

For news, notes and backstories on all things four-wheeled, visit our Auto History page.

5 Thoughts on “Who’s Driving That Parade Float?”

Leave A Comment

Comments are subject to moderation and may or may not be published at the editor’s discretion. Only comments that are relevant to the article and add value to the Your AAA community will be considered. Comments may be edited for clarity and length.

When I was about 6 years old (c. 1954), my great uncle took me to visit Louis Kennel, an old friend of his. Mr. Kennel was a painter and a designer of floats for the Macy’s parade. We visited him at his studio in Hudson County NJ. I saw floats and other decorations under construction. Best of all, Mr. Kennel gave us a couple of paper-mache heads that had been worn by marchers in earlier parades; one was a huge clown head and one a mouse.

When I was a teenager in New Orleans in the 1950’s, Mardi Gras floats were pulled by teams of mules. The drivers sat on the front of each float.

The Macy’s parade balloons were created by artist and puppeteer Tony Sarg who had been a window dresser at Macy’s in 1924. He then was enlisted to develop an idea that would entertain the crowds and decided on balloons. In partnership with Goodyear, his balloons debuted in 1927. Please give credit to the artist and puppeteer actually responsible.

Thanks for the additional info, Sharon (I was wondering who Tony Sarg was) – because his name *is* included on that Macy’s photo in the article.

Yes, glad that is there. He deserves credit. Nice to see so many people love a parade like I do, too. 🙂