Like nearly any other aspect of America’s past, countless names have been lost or forgotten through the years of the automotive industry’s history. More often than not, those names belong to people of color. Black pioneers have made innumerable contributions to the car world. Here are six trailblazers that steered the industry – and society as a whole – in the right direction.

Garrett Morgan

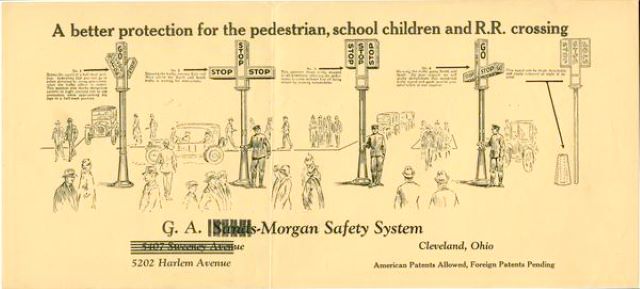

Invented the three-position traffic signal.

Born in Kentucky in 1877, Garrett Morgan would go on to become one of the great inventors of his time. By the 1920s he already had several inventions under his belt, including hair refiner and an early version of the gas mask.

Morgan’s success allowed him to own an automobile (reportedly the first African American in Cleveland to do so). After witnessing a terrible accident at an intersection, an idea was sparked.

Traffic signals had already been invented but they only consisted of two signals: “Go” and “Stop.” The problem was that drivers never knew when the signal was going to switch. This caused cars to stop abruptly or still be in the intersection when vehicles traveling in other directions began to move.

To solve this, Morgan invented a T-shaped traffic signal that had a third, “caution” signal, essentially a yellow light. When the “caution” signal was on, traffic in all directions stopped and intersections would clear. On Nov. 20, 1923, Morgan was awarded a patent for a three-position traffic signal. His original traffic signal prototype is on display at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History.

Aside from his technical contributions to society, Morgan was a pillar in Cleveland’s African American community. He founded the Cleveland Call, one of the most important African American newspapers in the country, and was a leader in the city’s NAACP chapter.

C.R. Patterson

Founded a company that would become the first African American-owned automobile manufacturer.

C.R. Patterson was born a slave in Virginia in 1833 but later escaped to settle in Ohio.

Patterson learned blacksmithing and worked for a carriage maker before co-founding his own business in 1873. For the next 20 years, the company ran a successful business making expertly crafted horse-drawn carriages.

In 1893, Patterson bought out his partner and formed C.R. Patterson & Sons. When he died in 1910, his son Fredrick took over the flourishing business as the transportation business was revolutionizing. The younger Patterson began noticing an influx of “horseless carriages” on the roads and knew that automobiles were the future. C.R. Patterson & Sons produced its first car in 1915. Known as the Patterson-Greenfield automobile, it sold for $850.

Patterson & Sons quickly established itself as legitimate auto manufacturer. According to the Historic Vehicle Association, the Patterson-Greenfield model was comparable in quality and workmanship to the Ford Model T.

There are no known Patterson-Greenfield automobiles in existence today, but several C.R. Patterson & Sons Company carriages have survived. The National Museum of African American History & Culture states that Patterson & Sons remains the only African American-owned automobile company in United States history,

Charlie Wiggins

Became one of the country’s great race car drivers, despite being barred from the Indy 500.

Born in 1897, Charlie Wiggins became an expert mechanic after apprenticing at a local automobile repair shop in his native Evansville, Ind. In 1922, he moved to Indianapolis, opened his own shop and built a race car out of nothing but junkyard parts. Nicknamed the “Wiggins Special,” it was his dream to drive the car in racing’s greatest event: the Indianapolis 500. But Wiggins was denied entry because of his skin color.

Undeterred, he and several other African American drivers formed their own racing league called the Colored Speedway Association. Wiggins’ exceptional driving and top-notch cars lead him to many victories, earning the nickname the “Negro Speed King.”

The highlight of the Colored Speedway Association circuit was the annual 100-mileGold and Glory Sweepstakes. According to the Historic Vehicle Association, the race’s 1924 debut drew a crowd of 12,000 – the largest sporting event held for African Americans up to that point. Over the next decade, Wiggins would win three sweepstakes championships.

In 1934, driver Bill Cummings hired Wiggins to tune his car for the Indy 500. Road & Track states that Wiggins posed as a janitor in order to elude Jim Crow laws. Thanks to Wiggins, Cummings won the Indianapolis 500 and set a track record.

Wendell Scott

Broke NASCAR’s color barrier.

Wendell Oliver Scott was born in Danville, Va., in 1921. He learned about cars from his auto-mechanic father. His first job was driving a taxi before he started running moonshine whiskey, which required him to drive fast in order to evade the police.

At the time, Danville’s racing scene was struggling with attendance. Owners thought recruiting an African American driver would help fill seats. They asked the local police for the fastest driver in town and in 1952, Scott became the first African American to compete in an official stock car race. He would go on to win 120 races in lower divisions, while continually being denied entry into NASCAR because of his race.

Then, in 1961, Scott was able to take over the auto-racing license of white NASCAR driver Mike Poston. He was officially a member of NASCAR’s top-level Grand National circuit – the first African American to do so. Just two years later, Scott became the first Black driver to win a NASCAR premier series event with a victory at the 100-mile race at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Fla.

By the end of career in 1973, Scott had accumulated 20 top-five finishes. The NASCAR Hall of Fame, into which Scott was inducted in 2015, lists his 495 starts 32nd on the all-time list.

Scott passed away in 1990. It would be another 23 years before a second African American, Bubba Wallace, won a NASCAR race, a full half-century after Scott accomplished the feat.

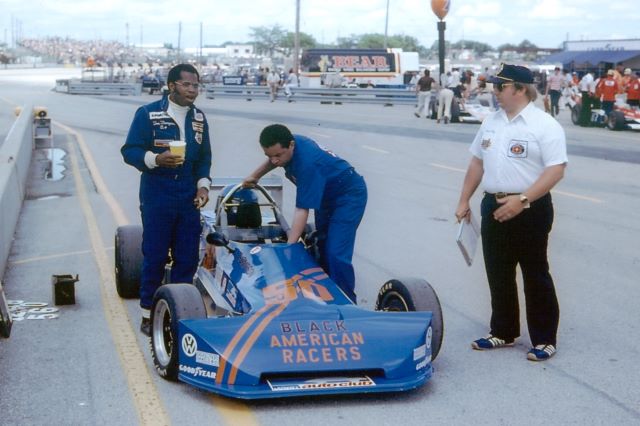

Leonard Miller

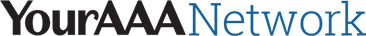

The first African American team owner to enter a car in the Indianapolis 500 and win a race in NASCAR.

Growing up outside of Philadelphia in the 1930s, Leonard Miller was introduced to automobiles at a young age through his mother, who worked as a housekeeper. “All of these rich, white families had all these rare cars that were beautiful and sounded good,” Miller told Smithsonian Magazine. “So, I said that was for me. And that’s what started me off to a lifetime of races.”

He would go on to pave the way for African Americans in the world of auto racing. It began when he formed Miller Brothers Racing, which won dozens of races throughout the Northeast from 1969 to 1971.

In 1972, he became the first African American owner to enter a car in the Indianapolis 500. Miller’s team was also the first Black professional race team to have a national sponsorship and to enter a Black driver in competition in England.

During this time, Miller also created the Black American Racers Association with, among others, Wendell Scott. The group promoted driver development and honored African Americans in auto racing. At its height, it included 5,000 members from 20 states and several racing disciplines.

With the help of his son, the automotive pioneer later founded NASCAR’s Miller Racing Group. The team won many races through the 1990s and early aughts. In fact, the father-son duo became the first African American team owners to win a track championship in NASCAR history with a victory at Virginia’s Old Dominion Speedway in 2005.

Miller was inducted into the Black Athletes Hall of Fame in 1973. Many of his awards, trophies and other memorabilia are currently housed at the Smithsonian Institute.

Homer B. Roberts

The first Black car dealer.

Homer B. Roberts was the first African American car dealer in the country but his greatest achievement occurred far away from the dealership. A veteran of World War I, Roberts was the first Black man to attain the rank of lieutenant in the United States Army Signal Corps.

Following the war, Roberts moved back to his native Kansas City and began selling cars. He specifically targeted selling to the African American community. In 1919, he put his first ad, for seven used cars, in the Kansas City Star, the prominent local Black newspaper. By the end of the year, he had secured 60 sales – all to Black drivers.

In the following years, business continued to grow. Roberts opened offices and showrooms and hired salesmen. In 1923, he opened a brand-new dealership named Roberts Company Motor Mart. Smaller automobile manufacturers saw potential in the African American market and backed his business. This helped Roberts land franchises with Hupmobile, Rickenbacker and Oldsmobile.

Hit hard by the Depression, the dealership closed in 1929 – but not before Roberts had etched his name in history.

McKinley Thompson Jr.

Ford’s first Black automobile designer

One day in 1934, while walking home from school in his hometown of Queens, N.Y., McKinley Thompson Jr. spotted a silver-grey Chrysler DeSoto Airflow. Although he was just 12 years old at the time, Thompson’s life was forever changed. “There were patchy clouds in the sky, and it just so happened that the clouds opened up for the sunshine to come through. It lit that car up like a searchlight,” he later told the Henry Ford Museum. “I was never so impressed with anything in all my life. I knew [then] that that’s what I wanted to do in life—I want[ed] to be an automobile designer.”

In the early 1950s, after serving in the Army Signal Corps in World War II, Thompson entered and won a design contest in Motor Trend magazine. His prize was a scholarship to the ArtCenter College of Design. After school, he went to work for Ford’s advanced design studio in Dearborn, MI. With that, Thompson made history by becoming the first African American automobile designer.

One of Thompson’s first projects was contributing sketches for the Ford Mustang. His most notable contribution, however, came in 1963 when he and other Ford designers conceptualized the Ford Bronco. According to the automaker, Thompson’s work “influenced the design language that would become iconic attributes of the first-generation Bronco.

“McKinley was a man who followed his dreams and wound up making history,” said Ford Bronco interior designer Christopher Young. “He not only broke through the color barrier in the world of automotive design, he helped create some of the most iconic consumer products ever – from the Ford Mustang, Thunderbird and Bronco – designs that are not only timeless but have been studied by generations of designers.”

What other Black pioneers in the automotive do you know about? Tell us in the comments below!

36 Thoughts on “The Black Pioneers of the Automotive Industry”

Leave A Comment

Comments are subject to moderation and may or may not be published at the editor’s discretion. Only comments that are relevant to the article and add value to the Your AAA community will be considered. Comments may be edited for clarity and length.

Ed Welburn was GM vice president of design from 2003-2016.

I read of Black-owned company (“Gallagher” ?) in Detroit that built truck and school bus bodies, yet went out of business during the Great Depression. 2/15/24

Richard Spikes was an African

American inventor and holder of eight patents. Patented between 1907 and 1946, Spikes’ inventions included an improved gear shift transmission system and an automatic brake safety system for buses and trucks. He is also widely credited with patenting automobile turning signals, first installed in 1910 on a Pierce-Arrow motor car (Black Past).

Great article–thanks for publishing this buried history!

I really enjoyed reading this article. I would love to read more like this. Thank you

Wow what a great article 2 thumbs up

Great article! Just one correction: The Black newspaper in Kansas City (Homer Roberts ad) was the Kansas City Sun, not the Star.

Great post AAA.

Great article! Add more next time!

Nice to learn more about my people’s history. I knew about Garrett Morgan, but didn’t know about the others. Thank you

You don’t remember Wendell Scott, Richard Pryor did a Movie playing him. Check it out it’s a good one.

Antron Brown started as a to drag bike racer. After running in 2 weeks he made the switch to 4 wheels and the rest is HIStory.

Antron Brown (born March 1, 1976) is an American drag racer, currently driving the Matco Tools Top Fuel dragster for Don Schumacher Racing in NHRA Camping World Drag Racing Series. He is known for winning 2012, 2015 and 2016 Top Fuel championships. Antron is the sport’s first Black American champion.

Top Fuel Cars are formerly called rail dragsters, they can accelerate from zero to 320 mph in 3.6 second in 1/4 of a mile.

Michael James

certified driving instructor

personal driving coach

How did you miss Ed Welburn??

Richard Pryor portrayed Wendell Scott in a movie some years back. I believe it was History Channel that did a piece on Garrett Morgan recently, around the gas mask. Very interesting! They made him be his own guinea pig.

Enjoyed this article on Black Pioneers of the Automobile Industry, I’d like share it , can you send me a copy without all the advertisements in it? Please send to my email, thank you.

thanks for reading! I just sent you a PDF of the page via email. Thanks again

Not sure how you do an automotive piece on this and NOT include the ONLY African American CEO of a fortune 50 (not 500) Automotive company. Rodney O’Neal was CEO of Delphi automotive. Not sure how this was missed.

I had no idea these pioneers in the automotive industry existed. This article proves black history is American history! Thank you so much for sharing.

Thank you for this story. It’s so amazing to see how much American history and African American history really are one history. The trouble is that much of “history” happens to neglect the fullness, really, the beauty of what is truly American history. Thank you

Thanks for this feature. I love that some trailblazers once ignored are getting some recognition. I hope that continues.

Just came across my AAA magazine from February 2021 and saw the link for the digital article on African American Automotive Trailblazers – WONDERFUL!

Last week, visited the LeMay Auto Museum in Tacoma, WA. Supposedly one of the best auto museums in the country, and an homage to the history of white America’s love affair w the automobile, it provided really NO information about the influence of automobiles on other American history. Sadly…. It didn’t provide as much information as contained in this article.

Wow, I loved this! Informative and captivating read.

Fantastic article! I didn’t know any of this – thank you for educating me!

The book, “First Black Autos” by Henry A. May, available from Stalwart Publications, Ltd. This book tells the historic story of the C.R. Patterson & Sons Company. The Pattersons were located in Greenfield, Ohio, where they manufactured cars, trucks, and buses. The also serviced and repaired vehicles made by other manufacturers.

Thank you for the much needed history lessons. They were interesting as well as informative.

Keep up the good work.

Very positive move recognizing Black history as American history. You don’t have to wait for February to publish articles like this. Carry on!

Thank you for this wonderful ,educational & ignored history .

Great info. I forwarded it to my daughter of whom loves cars as much as me and her grandfather may he S.I.P.

Check out Sellars Hall–Pittsburgh, PA. Inventions Tire changer

Who was first African American Automobile Dealer in Colorado? My father Charles E Howell Jr was allegedly one of the first if not the first. Any information on this matter would be helpful. Thank you very much!

My stepdad, african american automotive designer, McKinley Thompson Jr. Ford Motor Company

Hi, I just researched your stepdad and he sounds like a fascinating man. We will be sure to include him in our next article on the subject. Thanks for bringing him to our attention and thanks for reading!

I did not know any of this. Fascinating reading.

Glad you enjoyed Lorraine. Thanks for reading!

Great history.